This time a year ago I was stomping through the snow-covered streets of New York, slipping on ice and making sure to periodically move my toes so they did not freeze. I was cursing my unpreparedness for truly cold weather: no beanie, no gloves, and not enough layers. I was on my way to the Women’s Rights Caucus, a collective of progressive feminist individuals and organisations from around the world whose knowledge and expertise influence international negotiations on women’s rights issues. These early morning meetings, full of capable and committed women, were the saving grace of my turbulent United Nations experience. I was at my first Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), the annual United Nations forum that brings together member states and Civil Society organisations from across the world to discuss, debate, and decide on the future of women’s rights.

The challenge of CSW is that in two short week’s member states had to negotiate and come to consensus on the Agreed Conclusions: the final document that would lay out rights and obligations for all member states regarding the focus topic. The topic that year: “women’s economic empowerment in the changing world of work.”

I went into CSW feeling pumped! I was part of the World YWCA delegation – a large group of young women from places as diverse as South Sudan and Honduras, with the backing of a long standing and reputable women’s organisation. Being Australian, I was also fortunate that our Government and Civil Society organisations worked closely over the negotiations process. I had my game planned mapped out: attending Government and Civil Society events, soaking up knowledge from Women’s Rights Caucus elders, influencing negotiations through suggesting language and building relationships with representatives – it was an advocacy opportunity I had only dreamed of. And perhaps rightly so. As I soon discovered, my assumptions about women’s rights in the international sphere were completely and utterly wrong.

I feel I should be forgiven for thinking that the Commission on the Status of Women, would be a space for progressive thinking, and progressive people. This was my first mistake. From day one I was confronted with the unsettling reality that for every progressive women’s rights activist there, there was some conservative scumbug to match. Worse, these right-wing, conservative, anti-choice, anti-contraception, pro-“women should only be in the kitchen or making babies” individuals, were often well-resourced and in some cases in positions of power. I should note that this was the first CSW under a Trump administration, and Vice President Pence had the political savvy to appoint conservative anti-choicers as the official NGO delegates on the United States delegation. On top of this, you had the usual regressive suspects – the government from Saudi Arabia for instance – and my new favourite group to hate, Holy See – the Vatican’s delegation.

The power and influence of these people within negotiations should not be underestimated, and indeed contributed much to the degradation of robust language that would uphold women’s working rights. Trading off powerful language for weak language to gain American support was, under a Trump regime, inevitable.

Despite the people, the power and the watering down of language, what I found perhaps more distressing were the personal attacks made by right-wing conservatives on progressive spokespeople, and particularly those who were queer-identifying. This largely took the form of public shaming through verbal intimidation and harassment but also threats and acts of physical violence.

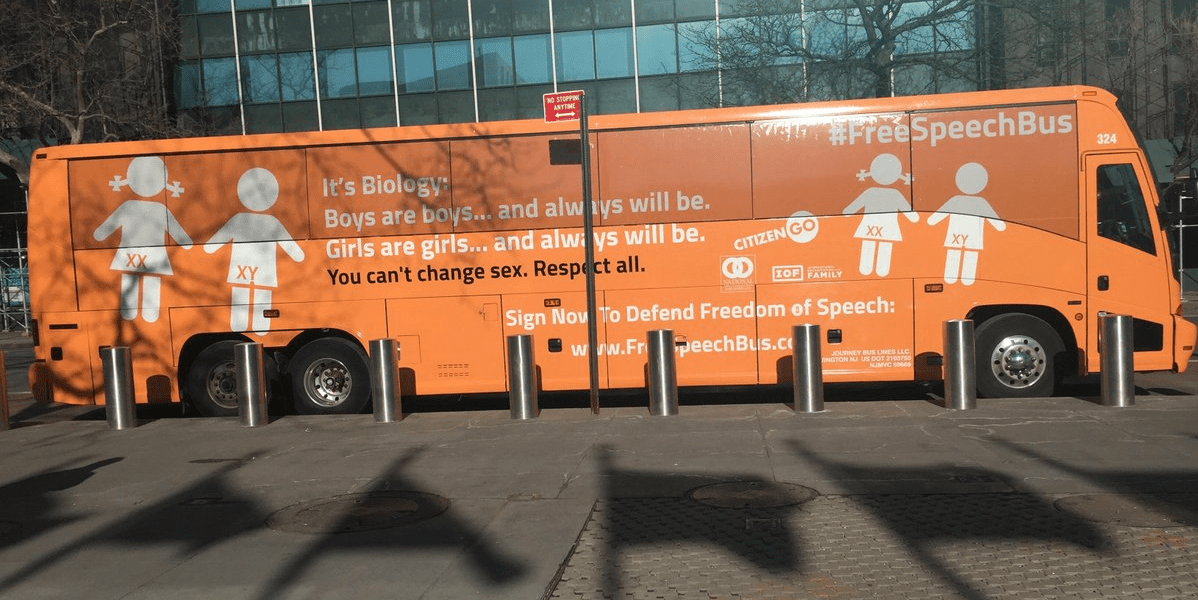

In addition to the targeted attacks on individuals, there was also public demonstrations. Notably, the “Free Speech Bus” better known as the Transphobic bus which espoused the gender-binary in bright orange outside the gates of the United Nations and essentially declared trans, intersex or gender diverse folk as non-existent.

The attacks on women’s rights filled me with rage and enough anger to fuel the long and often frustrating hours sitting in UN corridors or running around to meetings. During negotiations there were attacks on the most basic, but hard fought for rights, such as contraception, through to the complex and often contentious rights, such as regulating sex work. But perhaps what filled my heart with the greatest sadness and despair was the discussion of queer rights. So often the concerns of LGBTIQ people were marginalised, demonised and dismissed. The UN has been moving at a glacial pace in addressing these issues. Not having a forum like CSW to explore the rights of LGBTIQ people, or what is referred in human rights discourse as Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression (SOGIE), is perhaps the clearest indication of this. It has only been in the last year that the UN has appointed a Special Rapporteur for SOGIE –the only glimmer of hope I can see in an otherwise broken institution. Other than this, queer rights are a fringe issue at the UN – gaining minimal consideration at forums such as CSW.

My CSW experience was not the productive time I imagined: “women’s rights are human rights” was a statement most often found in rhetoric, not reality. A year on and I can finally look upon my experience with positivity, having become more resilient because of it, and more committed to playing an active role in being part of the solution. Whilst my experience might be disheartening, I would rather speak truth than see more people go in unprepared like myself. The truth is that we need more people fighting the good fight and we do ourselves a disservice by not preparing each other.

Amongst the difficulty, there were many memories to be truly grateful for: the humble, caring and intelligent young women I shared this experience with and the inspiring, strategic, and committed women’s rights activists that shared their knowledge and expertise. Coming into a Canberra autumn I can’t help but want to be back stomping through the icy New York streets and sharing with these amazing women the dream of a fair and just future, whilst doing our small bit to make it possible… and, if I can be honest, sticking it to an anti-choicer who is mortified that a single young woman has even been let out of the house.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.