Jessica Rombouts first considered that the Sumo Salad franchise she worked for might not be following the rules when her boss handed her an envelope of cash and told her she was going to be paid a “training wage” of $15 per hour.

That was more than $8 less than she was owed under her casual award rate, but Rombouts desperately needed the money so she didn’t challenge it.

For years, two Sumo Salad storefronts in Canberra — one at the Australian National University and another in Canberra City — have paid their workers as little as half of what they’re owed, and have failed to pay penalty rates, potentially robbing workers of thousands of dollars in unpaid wages.

How It Worked

Rombouts had just moved to a new city, started college, and was beginning her first year of university when she nabbed a job at Sumo Salad.

“I was desperate for a job,” Rombouts explained, “and it was only down the road from where I lived.”

And when they started paying her $15 per hour in cash, the young uni student didn’t know what to do.

“I didn’t really argue with it because I really needed the job.”

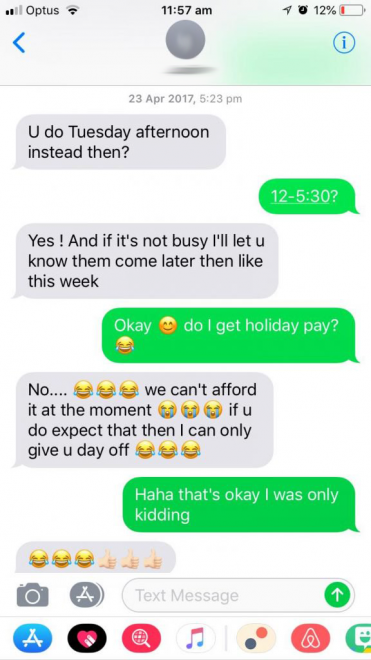

At first, Rombouts says, the franchisee didn’t even give her a contract to sign. And when Rombouts asked to be paid penalty rates on the weekend, as she was legally entitled to, her boss refused.

Even when the store hired a new manager at the end of 2016, Rombouts was still underpaid.

The Sumo Salad franchise got her to sign a contract that said she was a part-time employee, meaning she did not get the higher wage she would have received as a casual.

Payslips seen by Woroni show that even here, she was paid only $17.70 per hour, when the award rate for the lowest level of part-time adult fast food employee is $20.08 per hour. She still didn’t receive penalty rates.

And her fellow employees were even worse off. One current employee told Woroni that for the first five months of her employment, she was told she was in a “training period”, and was paid around $12 or $13 per hour as a result. Another employee told Woroni she was a trainee, on the same pay, for six weeks. Both workers wished to remain anonymous because they were worried about their employment being terminated.

Other employees often weren’t even given contracts to sign and would sometimes be given as little as six hours of work in a fortnight.

And even once Rombouts had left her job at Sumo Salad, the troubles continued. She realised that she had not been paid superannuation throughout her employment, and that she hadn’t been paid the annual leave she was owed as a part-time employee.

When she asked her boss about overdue payments “he explained that I did not have a super account connected to Sumo Salad”, despite super contributions being included in her payslip.

“How did [the manager] not know I was meant to have super, when he owns so many businesses?” Rombouts asked.

Rombouts did ultimately receive both her superannuation and annual leave, but only after weeks of pushing her former employer to pay her.

What Did Sumo Salad Know?

Sumo Salad head office has known about payment issues in at least one Sumo Salad store since February, when one employee emailed a three-page complaint to their operations manager, detailing concerns with issues such as the “training wage”.

A spokesperson for Sumo Salad said that many of the mistakes came down to a misunderstanding of the award by the franchisee, and that the company began an audit process within seven days of being alerted to the issues by staff members in February.

“Sumo Salad takes this matter extremely seriously and is committed to ensuring the wellbeing of all employees,” the spokesperson said in a statement.

But the spokesperson also acknowledged that there was a “gap” in the audit process because it did not take historical records into account, meaning some of the issues were not fixed until they were raised in a series of detailed questions earlier put to the company this week.

Some former Sumo Salad workers received backpay earlier this week.

“Sumo Salad has worked with the franchisee to ensure this matter has been dealt with in accordance with the Fast Food industry award, National Employment Standards & Fairwork act.”

The franchisee, Bryan Lai, said that he will “urgently fix any problems that are found”.

“We acknowledge that mistakes have been made in the past and we are working hard to fix anything that has not already been corrected.”

Why Does This Keep Happening?

Last week, it was reported that Melbourne’s Barry cafe was accused of underpaying staff by at least $5 per hour. The Fair Work Ombudsman is investigating the claims.

“Young workers make up about 16 percent of the Australian workforce but account for a disproportionately high 25 percent of requests for assistance to the agency. Last year 44 percent of the litigants we filed in court involved young workers,” Fair Work Ombudsman Natalie James said earlier this year.

“Young workers can be vulnerable in the workplace as they are often not fully aware of their rights or reluctant to complain if they think something is wrong.”

For international students attending university in Australia, the problem is even more evident.

According to a report from the Migrant Worker Justice Initiative, a quarter of international students earn $12 per hour or less.

While Fair Work does have an anonymous tip service, many fear that they would lose their job if the complaint was ever pinned down on them.

If you’ve been underpaid or exploited at work, get in touch with Max at max@woroni.com.au.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.