While thousands of kilometres divide Granada’s Alhambra and Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa mosque, they are united by a shared artistic heritage: that of Islamic Art. For many, Islamic Art conjures a monolithic oriental tableau of divine geometry, shaded patios, and shimmering works of tile. Indeed, while North Africa and West Asia have often been featured in Australian news reports as convulsive and divided lands, the popular Western perception of Islamic Art, that of a unified body of work, provides a unifying riposte to the news.

How correct is this perception? How unified is Islamic Art, and how valid is the term? In reference to these questions, I contend two claims. The first, that the term Islamic Art behaves like a “floating signifier:” it is a term that vaguely refers to many venerable artistic traditions in an unclear way. The second, that this floating signification begets a paradox: it is valid to refer to all of the traditions within Islamic Art as Islamic Art, but it isn’t to refer to Italian, Dutch, and French art as “Christian Art,” even though arguably Islamic Art displays more diversity than “Christian Art.” This is not to say Islamic Art doesn’t have its place as a term: however, there is great diversity that this term veils through its contradictions.

Firstly, what is a floating signifier? A signifier by itself is a particular form of individual thought, word, or sound that refers to the signified, the thing or concept that is being described. When I say “read the latest edition of Woroni,” the word Woroni is a clear signifier that refers to the signified, the latest edition of Woroni. A floating signifier, however, is a “a signifier with a vague, highly variable, unspecifiable or non-existent signified,” says Daniel Chandler. The way “socialist” is used to refer to all kinds of inconsistent political systems based upon how someone got out of bed, and nothing else (hahaha, just kidding…unless?) is a pretty good example of a floating signifier.

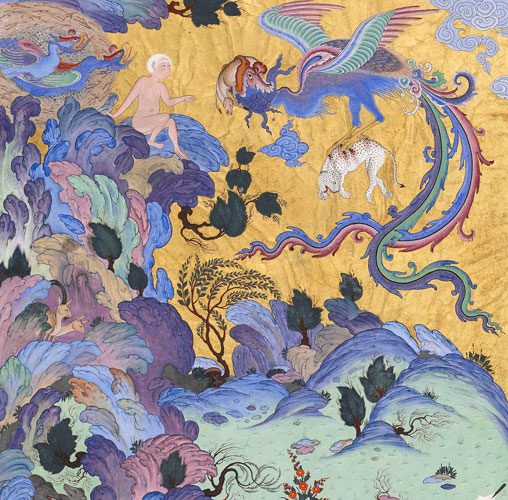

Why do I think the term Islamic Art is a floating signifier? Simply because it is logically a deeply contradictory term. The term “Islamic Art” implies that all its art is singular, while in reality its arts are spectacularly plural. For example, most instances of Islamic Art could be accused of being un-Islamic by different forms of Islamic Orthodoxy. It might surprise some readers, but in Iran, there are actual paintings (with faces!) of the Prophet Muhammad and Ali (a central figure in Shia Islam, and the rightful successor to Muhammad as Imam in Shia thought). Many Sunni sects would deem such art as haram and un-Islamic. Yet this is Islamic Art. This is an ambiguity problem. There is no internal logical consensus over whether certain kinds of Islamic Art are Islamic or not.

In the boundaries of the geographic Islamic Art world, there is also a problem of vagueness. The term Islamic Art implies that the art of places like Northern Iran, Azerbaijan, and Eastern Turkey should be more similar to the art of places like the Alhambra in Spain. However, miniature painting techniques, shared pre-Islamic myths, and a very specific Caucasian style actually tie the arts of these three regions to their Christian, non-Islamic neighbours: Armenia and Georgia. The Islamic Art of this region is more similar stylistically to its neighbouring Christian Art than Islamic Art from much of the Islamic World. How can some Islamic Art be more similar to some non-Islamic art then most Islamic Art? This continuum between the non-Islamic art of the Christian Caucasian world, and its Muslim neighbours creates a line drawing problem. Apart from the religion of the painter, the stylistic criteria that divide Islamic Art from non-Islamic art are often vague. Wouldn’t it be less vague to just call the art by what it is: Caucasian, Persian, or Turkish art? Much like it is done in Europe and the West?

Of course, this is not to discount the shared signatures of Islamic Art, such as the four-part garden, mosaic work and water features, which derive their origin from Persian, Byzantine, and Western Roman traditions. However, the diversity and multiplicity of Islamic Art are no different, if not greater, than those in the Christian or Western world. And yet, we seem to realise the dangers of applying a floating signifier to the art of the Western World by not referring to all of Western art as “Christian Art.”

In Islamic Art’s case, the contradictions inherent in the term suggest that an orientalist otherising-rooted in the same geopolitical and economic logic that created the Middle East-was responsible for the strength of the term.

This is why it is imperative that art collections in our neck of the woods curate art from across the Islamic Worlds. The cultural multiplicities, nuances, and contradictions are rich, beautiful, and often surprising. Clash of civilization theses, stereotypes about Islamic iconoclasm and dourness – these all become laughable when gazing upon miniatures of poets and scientists pouring wine, dishing out romantic advice, and playing games of chess. Since both Christian Art and Islamic Art suffer from floating signification, there is more to unite than divide. Long may artists honour this unity, and paint over the naysayers.

Think your name would look good in print? Woroni is always open for submissions. Email write@woroni.com.au with a pitch or draft. You can find more info on submitting here.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.