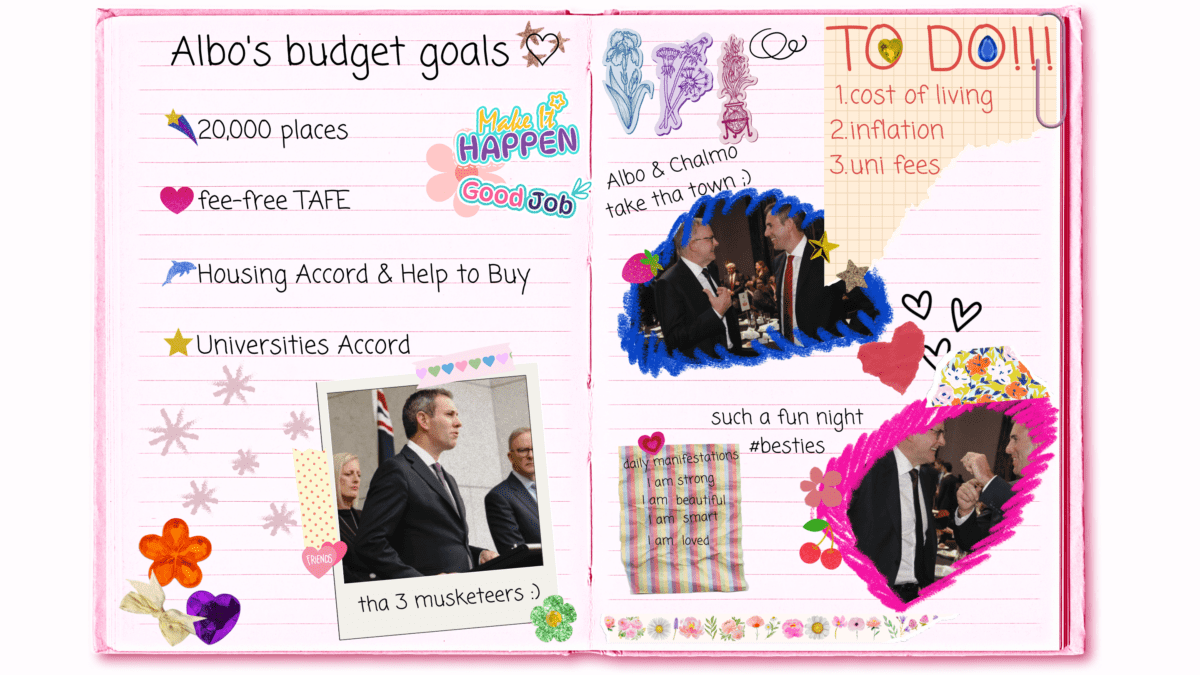

This week Labor released its first budget in nine years, and its first as the new government. Despite Labor’s long-term legacy as the party of accessible tertiary education, this budget was a disappointment for many university students.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers, in his budget speech, stressed that this budget was about building a more resilient Australia in the face of high inflation and a global economic downturn. It was, Chalmers claimed, about investing in, and protecting, Australia’s future.

Despite this, the budget spends underwhelmingly on University students, a key demographic in Australia’s future society and economy. Where there are policies to fix structural gender issues, such as paid parental leave, that have limited impact on inflation, there are few to assist students.

According to Andrew Norton, Professor in the Practice of Higher Education Policy, this budget “…was just Labor’s election commitments.” with no new policy for universities. Senator Faruqi, the Greens member for higher education, summarised the budget as not putting in “… the massive investment that universities need.”

Below, Woroni outlines the forward-looking aspects of the budget, to ask what kind of future the government is creating.

20,000 More Places

The educational highlight of Labor’s budget was funding 20,000 more places for low-SES, rural and regional, first-in-family, students with a disability, and First Nations students. It was the only policy that the government brandished as improving access to tertiary education in Australia.

However, the policy itself will likely have a mixed impact on accessing university. Getting to university can be a difficult step for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. However, it is only the first step. Equally important are the supports that exist around university which help ensure that disadvantaged students can actually make it all the way through their degree.

Two-thirds of students already live below the poverty line. Without improvements to welfare support like Youth Allowance, and without efforts to address rental prices for students, any funding for disadvantaged students will not address structural inequality in higher education.

Senator Faruqi, speaking to Woroni, agreed that access was only one issue of higher education. The Senator argued that the budget’s lack of support for low socioeconomic people is a “…pretty terrible thing where students and universities are concerned.”

In the lead-up to the budget, other parties and activists laid out clear ways that the government could assist students. Senator Faruqi’s own bill to stop indexing HECS-HELP fees to inflation would prevent the substantial jumps to student debt that occur in high-inflation environments.

Alternatively, the National Union of Students (NUS) argued for raising the Youth Allowance amount to $88 a day, in line with the Henderson Poverty line. Youth Allowance currently sits below the median wage, the Henderson Poverty line, and the JobSeeker payments. As the NUS emphasised at a protest and marriage ceremony this week, students receive more government support if they marry another student.

Policies like raising youth allowance would help to make university more accessible. The HECS-HELP scheme means that the most prevalent barrier to university would be the cost of living, a situation the current budget does little to solve.

When Woroni spoke to Professor Andrew Norton he confirmed that the 20,000 extra places will have little impact on university accessibility. He called the policy “stranded funding” because students who want to access the money must go to university, come from a disadvantaged background, and be willing to study the specific programs. As Norton put it, “If any one of these three conditions cannot be met, the money won’t be used even though it could be if there was more flexibility in the system.”

TAFE and Skills Shortages

Vocational training and skills shortages appeared throughout the budget. The government plans to establish a Jobs and Skills Australia advice body, and has designated a substantial $921.7 million over five years to be spent on fee-free TAFE places. These places are to target industries and regions lacking skilled workers.

Senator Faruqi expressed to that, “TAFE and university should be free for everyone… It’s not a choice between who gets more money, who gets more places.” While TAFE is understandably needed, there are also substantial economic benefits to investing in universities. For every dollar put into the tertiary sector, $5 dollars go back into the economy. Such investment would have a small impact on inflation and could have accompanied policies like the reduction to the cap on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and paid parental leave.

Like the 20,000 new Commonwealth Support Places, access to TAFE is also reserved for the study of disciplines with skills shortages.

In having one catch-all requirement to target both disadvantaged students and areas of skills shortage, the policy, like the Jobs Ready Graduate package, does little to alleviate choice inequality. Students with less financial means are limited in study options, while higher SES students are still able to access the full range of offerings.

While Australia’s current skills shortages are a major concern, policies which aim to address skills shortages and accessibility simultaneously run the real risk of failing at both.

Rental Affordability

Housing was the centre-piece of both the Labor and Liberal-National budgets this year, and both framed it as achieving the Australian dream. For students, many of whom will not think of buying a house for years, there is little in this budget to help with paying rent.

Announcements such as the Housing Accord, which aims to build one million new homes, and Help to Buy, a scheme to aid low and middle income earners to purchase a home with a government contribution, were largely focused on housing affordability. Labor made no announcements about direct intervention in a rental market where only 0.9 percent of properties are vacant.

The inclusion of social and public housing in the Housing Accord may be promising for students who need to access this type of accommodation. However, the policy includes just 20,000 houses fully-funded by the government and another 35,000 to be part-funded. This is a small fraction of one million, and is an underwhelming start to the policy. The majority of these houses are likely to be unavailable to students, either because they are too expensive, or because they are built by property developers who favour full-time workers and families. Younger Australians, particularly those at universities, feel the brunt of Australia’s housing crisis. They are more likely to experience any of this policy’s failings.

The government assumes that increasing the supply of houses will drive prices down, including rent prices. However, sluggish wage growth means that house prices would have to drop precipitously to where they were several years ago. Supply is one issue, but the government also needs to assist demand in order to balance the housing market.

Rent prices and the lack of public housing will continue to impoverish the youth in Australia if the government does not address them. Skyrocketing rental prices due to inflation, with no increase in support measures like Youth Allowance, leaves students paying more for the simple necessity of a place to live.

Universities Accord

The budget likely has not touched higher education because the government is set to announce the terms of reference for the Universities Accord mid-next month. Labor is pitching the Universities Accord as driving “lasting reform at our universities.”

What this actually means is currently unclear. The government has said little about what the structure of the accord will look like, and how it will be established and maintained if successful. However, in 2019, then shadow education minister Tanya Plibersick summarised the accord as:

“…a partnership between universities and staff, unions and business, students and parents, and, ideally, Labor and Liberal, that lays out what we expect from our universities. […]”

This has led to speculation about what is on the table and what is not. ANU’s Vice-Chancellor Brian Schmidt has put “uniform” student contributions and research grants and freedom at the centre of his agenda for the Universities Accord. Schmidt also rejects the ethos behind the 20,000 places policy: that students need to be guided towards the skills Australia has a shortage in.

Andrew Norton is also confident that student contributions will be an item in the Universities Accord. The Labor government has remained largely silent on the fee hikes in the Job Ready Graduates Program. The Universities Accord could be its way of winding back the economic inequality currently instilled in the university funding system.

Not Quite There

Senator Faruqi described the budget as “better than we’ve had for a very long time,” which is not to say that it tackles the issues many had hoped it would. It is a budget off the back of an election where Albanese is trying to maintain his election promises and appear as the Prime Minister of responsible government. What the bigger changes, including future budgets and the Universities Accord, achieve for students remains to be seen.

Woroni reached out to Jason Clare MP, Minister for Education, and to Senator Katy Gallagher, the Minister for Finance, for comment. Both declined.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.