Suppose you take two of your friends—let’s call them Arthur and Mark—to the kennel to buy a new dog. The owner of the kennel explains that they have just two dogs left and that these dogs are identical in every way except for their personalities. “Their personalities?” you ask, curious to find out more. The owner says that the first dog is “really quite gentle, friendly to strangers, independent-minded and often relates to its owner as an equal.” The second dog is “very obedient and easily trained. He does not open up quickly to strangers, but once he gets to know you, he is fiercely loyal.” Upon hearing this, Arthur says he wants the first dog, and Mark says he wants the second.

Based on this, which one of your friends do you think is more likely to have voted for Joe Biden, and which one for Donald Trump, in the 2020 US presidential election?

Well, researchers have examined a very similar question as part of their investigation into Moral Foundations Theory (MFT). MFT is a new psychological theory that argues that human moral reasoning is based on at least six innate ethical intuitions: care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, sanctity/degradation, and liberty/oppression. The theory was first proposed by Jonathan Haidt, Craig Joseph and Jesse Graham after finding that experimental subjects often approved or disapproved of hypothetical ethical scenarios before any conscious reasoning process. For example, in one paper titled The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail Haidt noted that although his experimental subjects found certain harmless norm violations wrong (such as secretly using an American Flag to clean a bathroom) they could not rationally justify such beliefs when pressed to do so.

Haidt concluded that this is because most moral judgement is based on innate intuitions that humans have evolved to help them cooperate better in large groups, rather than being based on reasoning alone. Psychologists have long observed that people make decisions using unconscious heuristics. Daniel Kahneman documents this quite well in his book Thinking Fast and Slow, exploring intuitions and biases such as loss aversion, availability bias, and the endowment effect. These heuristics tend to be useful from a survival standpoint—they save significant time and cognitive energy to produce a decision that is often beneficial. Moral Foundations Theory extends this idea to ethical decision-making. By drawing from anthropology, primatology, psychology and extensive empirical evidence, the theory argues that the six foundations listed above are the basis for these moral intuitions.

The following table summarises the foundations and their proposed social function:

| Foundation | Definition and social function |

| Care/harm | Represents our intuitive dislike of unnecessary suffering and our sensitivity to pain in others. |

| Fairness/cheating | Represents notions of fairness, justice and reciprocity. This foundation condemns unequal treatment and inequality. |

| Loyalty/betrayal | This foundation condemns betrayal and praises self-sacrifice for the ‘greater good.’ It manifests itself through notions of group affiliation (such as sporting teams, political parties, countries etc.). |

| Authority/subversion | Represents notions of fulfilling social roles, respect for hierarchy, traditions and strong leadership. Encourages deference to legitimate authority. |

| Sanctity/degradation | Represents notions of purity and contamination and underlies notions of striving for a noble/elevated life. Sanctity/degradation implies that certain things must be treated in certain ways given their inherent value, and can apply to objects, places, ideas, behaviours and other people. |

| Liberty/oppression | Represents the feelings of resentment people feel towards those who restrict their freedom. |

Figure 1: The Moral Foundations Theory Table

The links between the moral foundations and politics have proven significant. In a series of global surveys (a version of which is available at yourmorals.org) Haidt and Graham found that, regardless of country or culture, those who identify as liberal have a “three-foundation morality,” where they primarily endorse the care/harm, fairness/cheating and liberty/oppression foundations. The more conservative you are, the more likely you are to endorse the other three foundations (loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion and sanctity/degradation). Importantly, conservatives have a six-foundation morality—they endorse all foundations relatively equally.

This finding was true no matter how the question was asked. Returning to the question at the beginning of this article, Haidt and Graham found that liberals prefer dog breeds that relate to their owners as equals (liberty/oppression) and are gentle (care/harm), whilst conservatives want dogs that are obedient (authority/subversion) and loyal (loyalty/betrayal). Interestingly, both sides prefer clean dogs (sanctity/degradation). Judging from this, Arthur probably voted for Joe Biden, and Mark for Donald Trump.

Another study in 2011 by Ravi Iyer found that liberals tend to be more disturbed by signs of violence and suffering (care/harm) than conservatives. In 2010, Graham discovered that these differences can be detected in brainwaves, with EEG (encephalogram) scans revealing that liberal brains show more shock when flashed sentences that reject care and fairness in favour of loyalty, authority and sanctity. In 2015, Andrew Franks and Kyle Scherr found, using regression analyses, that knowing someone’s moral foundations is a better predictor of voter choice than traditional demographic variables (race, gender, income etc.).

Moral foundations have also proven powerful in developing individuals’ political perceptions. For example, one study by Mathew Feinburg and Robb Willer in 2012 found that liberal discourse about environmentalism is largely framed in terms of the care/harm foundation (such as harm to those living in developing nations, harm to animals, harm to the planet etc.). However, when framing pro-environmental rhetoric in terms of sanctity/degradation (a mostly conservative foundation), the difference in liberal and conservative environmental attitudes was largely eliminated. Essentially, if we wish to gain more agreement in politics, we need to start speaking each other’s moral languages.

Of course, this all implies that political parties could be more successful if they framed their political issues in as many foundations as possible. So far, a few studies have found that this is true in the USA. For example, Joel Hanel found that Democrat and Republican candidates did better in opinion polls if their advertisements used the full range of moral foundations. However, in his book The Righteous Mind (2012), Haidt laments that in recent times the Democrats have failed to take full advantage of all six foundations. Instead, they have focused almost exclusively on care/harm, fairness/cheating and liberty/oppression.

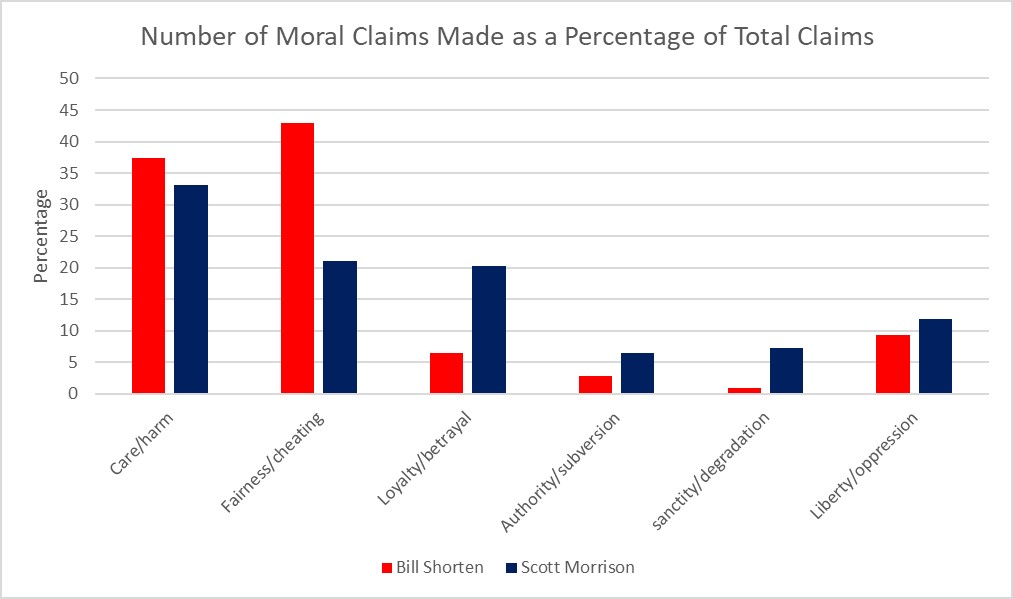

I was interested to see if this was also the case for the two major political parties in Australia—the Australian Labor Party (ALP) (Australia’s primary liberal/left-wing party) and the Liberal Party of Australia (Australia’s primary conservative/right-wing party). There were no studies looking into the Australian case that I could find, so I decided to conduct my own analyses as part of a research project for one of my political science courses. To see how each party was using the moral foundations, I analysed the campaign launch speeches of Bill Shorten (then leader of the ALP) and Scott Morrison (then leader of the Liberal Party) during the 2019 federal election (at the time, the 2022 election had not taken place). I decided to use the federal campaign launch speeches for their representative value—each politician is representing their whole party on a national scale and each speech is addressed to the Australian public in general.

To see how the leaders framed political issues in terms of the six foundations, I went through each speech in detail, and every time I found a moral claim, I coded it into one of the six moral foundations. This is a method common in qualitative research called content analysis. As an example, see the table below:

| Moral Foundation | Example |

| Care/harm | “I make this promise to my fellow Australians…help with the cost of living for families, including cheaper childcare” (p 1) Bill Shorten |

| Fairness/cheating | “if you vote Labor, we will put the fair go into action” (p 1) Bill Shorten |

| Loyalty/betrayal | “They sacrificed and they also served” (p 1) Scott Morrison |

| Authority/subversion | “A country where older Australians are respected…” (p 3) Scott Morrison |

| Sanctity/degradation | “A country where you can live in an environment that is clean and healthy and the envy of the world” (p 3) Scott Morrison |

| Liberty/oppression | “it’s also a country that… unceasingly strives to ensure that every Indigenous girl and boy can grow up with the same opportunities as every other Australian” (p 3) Scott Morrison |

Figure 2: Coding Examples

After taking the frequency of each claim, I created a bar chart showing the percentage distribution of each claim type. By looking at the percentage each foundation makes of the total claims made, we can get an idea of the relative importance each foundation has to each politician. For a full methodological breakdown and discussion of limitations click here to view the original paper.

The results were as follows:

Visual inspection of the bar chart reveals that Morrison’s moral claims are more evenly spread across the six foundations than Shorten’s. This is largely what we would expect given the MFT literature. However, it appears neither leader is maximising their use of the moral foundations: both leaders made few references to authority/subversion, sanctity/degradation and liberty/oppression (for a full discussion of results, see original paper). This suggests that both parties could benefit from framing political issues more evenly across all six foundations.

Since at least 1993, the major parties had been receiving around 80 per cent or more of first preference votes in the House of Representatives. In 2016 they received 76 per cent, in 2019 74 per cent, and in 2022 just 68 per cent (the lowest on record). Perhaps a greater utilisation of the full moral spectrum could help draw voters back to these centre-left and centre-right parties.

To conclude, our moral foundations shape much of our political ideology. This can be divisive if we ignore the types of moral matrices our political rivals see the world in, or it can be greatly unifying if we learn to speak each other’s moral languages. In Australia, there is some divide between how each party morally frames political issues into the six foundations, however, both could benefit from wider employment of all foundations.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.