Adaptations are a tricky business for any filmmaker. Regardless of the text you are adapting, there will be a dedicated fan base for the original source material who will be both the first in the cinema to watch your creation, as well as the ones most eager to tear it apart. I found myself in this position after reading Louisa May Alcott’s coming-of-age novel Little Women.

In typical bildungsroman fashion, Little Women follows sisters Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy March from childhood to adulthood. Originally published in two volumes in 1868 and 1869, the story was heavily inspired by the author’s own childhood and family. Since its publication, the novel has been well loved by readers for its honest portrayal of sisterhood, love and self-discovery.

In 2019, the novel was once again adapted into a film by renowned director Greta Gerwig. At the 92nd Academy Awards, Gerwig’s film was nominated for several awards, including Best Picture and Best Adapted Screenplay. Naturally, I was very excited to watch this so-called masterpiece.

However, I was sorely disappointed. Gerwig made considerable changes to the structure of Alcott’s novel and to her characterisation. While changes are inevitable in transplanting hundreds of pages of writing into two hours of screen time, they have to make sense. If a change is nonsensical, it risks undermining the authenticity of the adaptation and calls into question the adaptor’s understanding and interpretation of the text.

One major change in Gerwig’s Little Women was the decision to alter the timeline of the book. Instead of beginning during the sisters’ adolescence and ending during their adulthood, Gerwig’s film flits between two narratives; the childhood sequences serve as flashbacks to the main adult storyline. This, I believe, renders mute the major themes of the novel: family and growth. As readers, we watch the March sisters grow and develop as the eponymous “little women”. Many of the chapters in Part One of the novel involve the sisters learning moral lessons through their mishaps and misjudgments. For instance, in “A Merry Christmas”, the sisters are exposed to the value of sacrifice. In “Amy’s Valley of Humiliation”, Amy faces the consequences of disobedience and conceit, while in “Jo meets Apollyon”, Jo is shown the importance of patience and self-control. This depiction of personal growth is undercut by bringing the adult storyline to the forefront. The girls’ childhood is not meant to be merely fodder for character development; it is integral to who they are as women. Their familial and sororal bonds are the driving forces behind their entire existence.

In a similar vein, Marmee — the mother of the March sisters — is horribly characterised. During the years of the American Civil War, she is the main caregiver of the girls as her husband is serving as a chaplain for the Union Army. Alcott’s Marmee is the guiding light for both her children and the reader; she epitomises all she preaches. She allows her daughters to make mistakes and then helps them learn from the error of their ways. She teaches them what is important and good and right in a way that makes them (and the reader) want to (or at least try to) obey because they know they will be all the better for it.

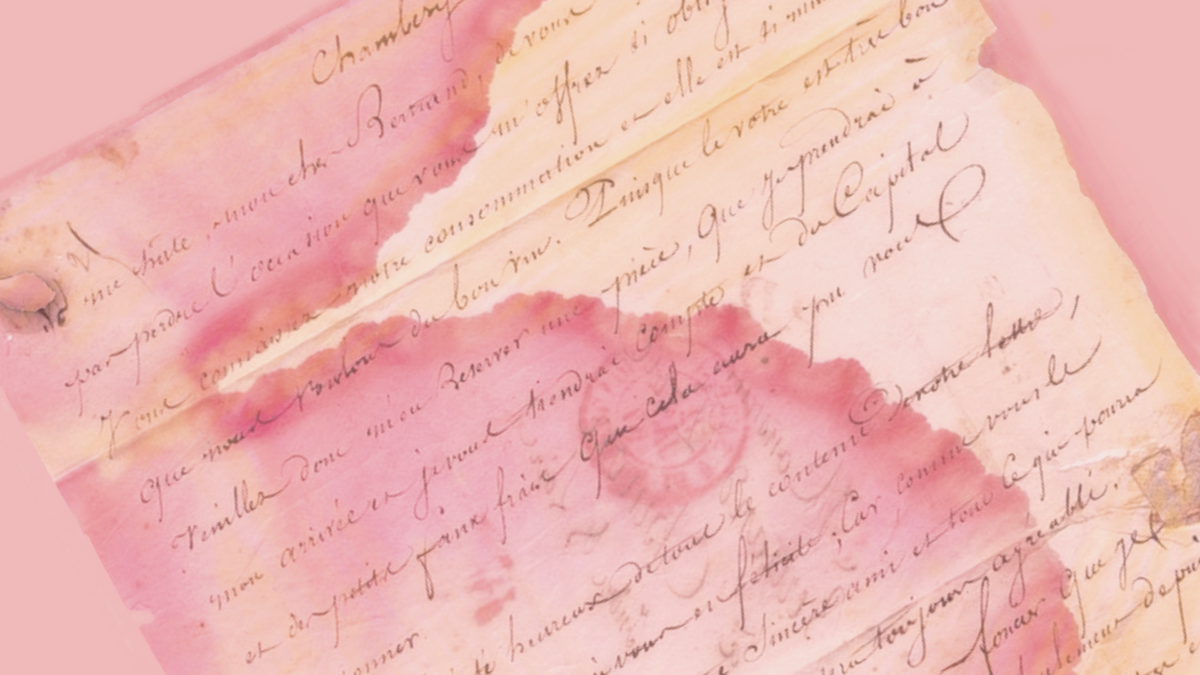

Gerwig’s script is written in such a way that Marmee, despite being played by the incredibly talented Laura Dern, fades into the background in every scene instead of being the central force that her daughters gravitate towards. Her dialogue is reduced to backhanded quips at her husband for a reason that is difficult to identify. Perhaps this is Gerwig attempting to add comedy or perhaps it’s her not knowing how to subvert a relationship that is already quite subversive. The marriage between Mr and Mrs March is meant to be one of love, devotion, adoration and equality. Alcott’s Marmee is imbued with agency and wisdom; she is respected by all who meet her. The essence of her role in the family is established in the very first chapter as Marmee reads aloud the letter sent by Mr March: “They all drew to the fire, Mother in the big chair with Beth at her feet, Meg and Amy perched on either arm of the chair, and Jo leaning on the back”. Gerwig seems to believe that Marmee cannot embrace these principles in a film set during the 19th century so she must resort to making sharp retorts to whatever her silly husband says to assert her authority.

The film also makes the mistake of attempting to adapt Little Women in line with contemporary standards of feminism, ignoring the fact that the novel is already subversive for the time period and place in which it was written and set. In one of the film’s early scenes, Jo responds angrily to Friedrich Bhaer, a German professor who is staying at the same boarding house, when he criticises her writing. Jo’s reaction, while stemming from hurt, is illogical. Jo is writing ‘sensationalist’ stories for a newspaper to make money; importantly, she elects for the stories to not be printed under her name. In the novel, she hides this occupation from her mother because “she was doing what she is ashamed to own”. Jo does not need to ask Bhaer his opinion because she shares it already. She eventually quits writing sensationalist stories, musing “I almost wish I hadn’t any conscience, it’s so inconvenient. If I didn’t care about doing right, and didn’t feel uncomfortable when doing wrong, I should get on capitally.” The director instead appears to have re-imagined this scene from a “feminist” lens; Jo can write whatever she pleases, Gerwig seems to be saying, and how dare Bhaer judge her when he knows nothing about literature! This representation has no footing when we take into account that in the source text, Jo and Bhaer’s views on the matter are aligned.

Just because Alcott’s novel does not embody that which we perceive as feminism today, does not mean that it is not a subversive representation and examination of womanhood. The sisters were never restricted by their gender, at least not by their parents. They were not forced to conform to societal standards of womanhood. They stayed true to who they were. The novel centres on familial love, it promotes empathy and compassion, it encourages the reader to — like the sisters — to be the best version of themselves. It is very empowering to read a novel about four sisters who love each other dearly and who have a strong maternal figure that cares exclusively for their happiness. Marmee does not need to assert her authority by shaking her head mournfully at her husband’s idiocy, and the “tom-boy” sister does not need to prove her agency by disagreeing with something that she fundamentally agrees with.

Gerwig also struggles to authentically represent the progression of Amy and Laurie’s relationship from childhood friends to two young people in love. In one line, Amy contends that she has always loved Laurie. However, none of the flashbacks in the film even hint at a romantic affection harboured by the young Amy. Similarly, the two seem to be just pushed together and suddenly declare their love for each other. This fails to capture the mutual respect and adoration that develops while the two characters write letters to each other while in Europe. Jo’s rejection of Laurie also fits awkwardly within the narrative, creating an uncomfortable love triangle. After Beth’s death, Jo reveals that if Laurie were to ask her to marry him again she would say yes. She even writes him a letter, but hurriedly removes it from his mailbox after discovering he has married her sister. Here, Gerwig misinterprets the effect Beth’s death has on Jo. The death does not suddenly make Jo realise that she does in fact love Laurie or that she desires to get married. Instead, the loss of her sister opens herself up to experiencing a different kind of love that she has not yet felt.

A novel worthy of an adaptation is naturally loved for what it is, so the question stands: why do filmmakers make these changes? In May, George RR Martin wrote a post on his “Not a Blog” blog, titled “The Adaptation Tango” that appeared to answer this question. He makes excellent observations from the perspective of an author who is no stranger to his work being adapted (and butchered). He states, “Everywhere you look, there are more screenwriters and producers eager to take great stories and ‘make them their own’.” Regardless of who the author is or how great their work is, he says, “there always seems to be someone on hand who thinks he can do better, eager to take the story and ‘improve’ on it.” He finishes with: “They never make it better, though. Nine hundred ninety-nine times out of a thousand, they make it worse.”

Gerwig’s Little Women has been enjoyed by audiences, and for that I am glad, especially if they felt the same joy as I did reading the novel. Yet, I cannot help but feel that it is almost disrespectful to mischaracterise an author’s creation for your own monetary gain.

Of course, Gerwig is not alone in this. Adaptations have been criticised, crucified, and torn to pieces for years past, and will be in years to come. Netflix recently announced that they were adapting Oscar Wilde’s masterpiece, The Picture of Dorian Gray, but instead of remaining true to his queer construction of Basil Hallward and the titular protagonist, the characters are instead to be made siblings. This seems particularly troubling as Wilde was imprisoned for homosexuality, with excerpts of the novel used as evidence to convict him. Emerald Fennell is also set to release her own adaptation of Emily Bronte’s Victorian gothic, Wuthering Heights, although no details on that project have yet been revealed. It appears that as long as the written word remains, the adaptation tango will too keep on going.

We acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Woroni, Woroni Radio and Woroni TV are created, edited, published, printed and distributed. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge that the name Woroni was taken from the Wadi Wadi Nation without permission, and we are striving to do better for future reconciliation.